Our latest post in the SaaS attacks matrix series is focused on external phishing via Slack. Unlike email, IM apps and the messages within them are typically more trusted by employees, making social engineering via Slack a juicy target.

Our latest post in the SaaS attacks matrix series is focused on external phishing via Slack. Unlike email, IM apps and the messages within them are typically more trusted by employees, making social engineering via Slack a juicy target.

This is the third post in a series on attack chains formed by combining techniques in the SaaS attack matrix. Last post we wrote about shadow workflows and evil twin integrations.

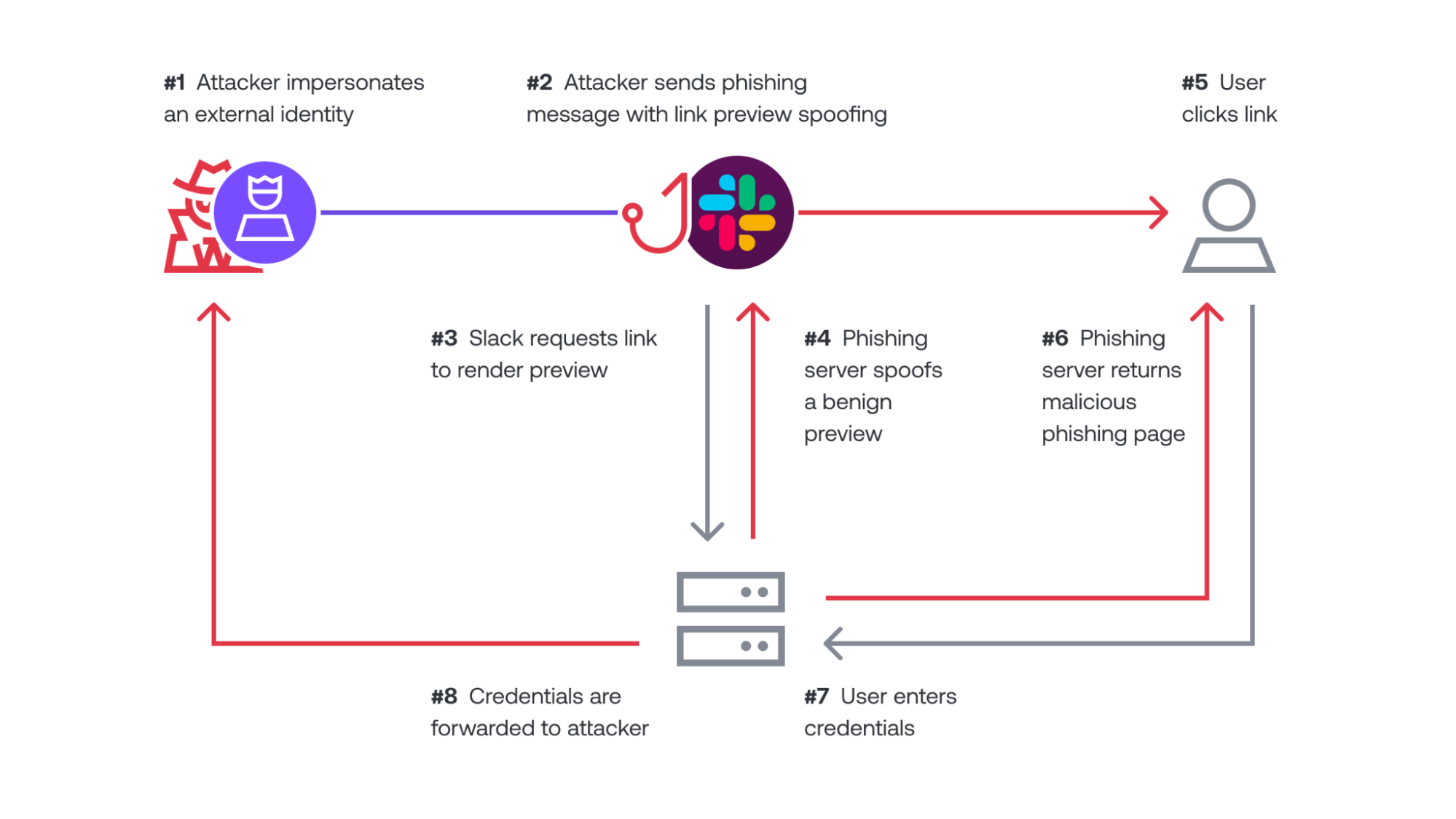

In this article, we’ll demonstrate how instant messaging applications are an increasingly attractive target for a range of phishing and social engineering attacks. We’ll use the following SaaS attack techniques chained together:

We’ll use Slack as our primary example in this case and we’ll be primarily focused on external phishing as part of the initial access phase of the kill chain.

In the companion article, we’ll look at how once an attacker has a foothold on Slack, new attack possibilities open up that allow for persistence and lateral movement to be achieved.

Why focus on instant messengers?

They aren’t new, however, the original focus of IM apps was on internal communication and phishing and social engineering attacks are often external. Email remained the standards-based protocol that enabled external communication no matter what email vendor was in use. In recent years, however, instant messengers (IM) have become the primary method of communication for many businesses. I wanted to focus on IM here because if that’s where employees are communicating, it’s the best place to launch attacks against them. Even better, there’s a history of users placing a higher degree of trust in IM platforms than email, so it becomes a potentially easy target.

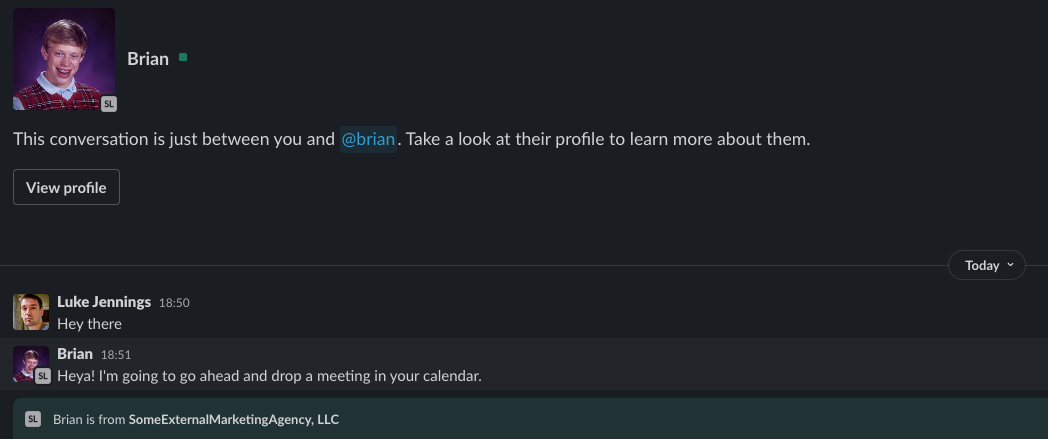

While IM platforms were initially used solely for internal communications, organizations quickly realized that IM platforms could be used to communicate with external groups, individuals, freelancers, and contractors, with the hope of fewer emails and more instant communications.

We now have Slack Connect and Microsoft Teams external access to support this, with Slack Connect introduced in June 2020 and Teams introducing it in January 2022. This external access has increased the attack surface of these platforms considerably.

Despite decades of security research, email security appliances and user security training, email-based phishing and social engineering is still commonly successful. Now we have instant messenger platforms with:

Richer functionality than email,

Lacking centralized security gateways and other security controls common to email and

Unfamiliar as a threat vector to your average user compared with email.

There’s also a sense of urgency associated with IM messages due to the conversational nature compared with emails. Combined with a history of increased trust, we have the ingredients for increased social engineering success.

There’s been an uptick recently in IM-based phishing research and real-world attacks, particularly for Microsoft Teams. For example, check out the great research from JumpSec on bypassing attachment protection for external Teams messages, the offensive tool TeamsPhisher and attacks distributing DarkGate malware via Teams.

However, in this article we’ll focus on a few techniques specific to Slack.

IM user spoofing

The first consideration is the spoofing aspect. We’ve all seen techniques for spoofing emails, but there are many security controls like Sender Policy Framework (SPF) that can prevent direct spoofing of domains and email security gateways that can flag suspicious domains.

Those security controls don’t exist for IM, so we have new options for spoofing.

External IM invites

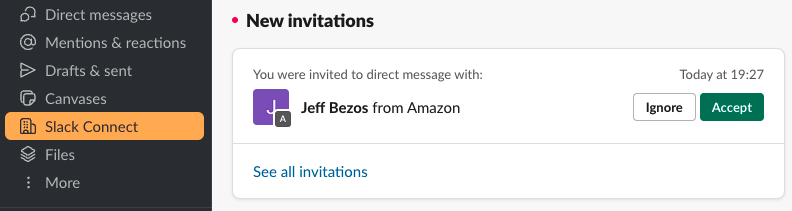

IM applications often make use of friendly display names for organization and employee names as well as user-chosen handles. These often don’t need to be unique either. Consider the following Slack Connect request:

It’s not easy for a target user to tell if the user or organization requesting to connect is legitimate when they first receive this invitation. There’s also a curiosity incentive - you can’t see a first message from the user, so it’s tempting for the target user to accept in order to see the message, even if they then ignore it.

However, once an attacker has got a first connection, they have cleared the first hurdle. They can now launch attacks in future, not just attacks immediately following a successful connection, after the target user has forgotten they ever connected with the attacker (more on this later).

Spoofing an internal user

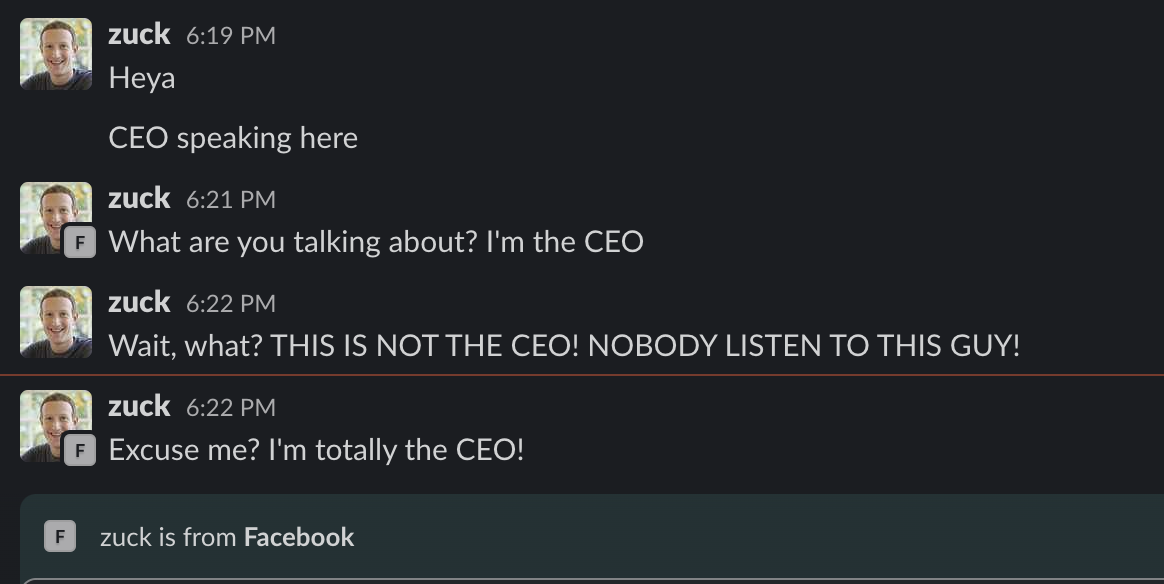

What’s more, there’s nothing stopping an external attacker from impersonating internal users/employees too. This is especially a concern if an attacker can social engineer their way into being invited into a channel.

While this particular example is less likely to be successful in a small channel, it’s much more of a concern if they change their user identity to replicate an internal employee or teammate and then direct message a member of the channel. DMing an individual channel member doesn’t require a new Slack connect invite so it’s much easier for an unsuspecting target to fall victim to social engineering in this way.

Chameleon attack

A particularly interesting external attack capability is that an attacker can act as a chameleon and change their identity over time. Let’s say an external attacker achieves a successful connection with a potential target as an external entity. Maybe they exchange some innocuous communications and then leave the conversation to die. Perhaps the target even has Slack message retention settings enabled that delete the chat history after 90 days.

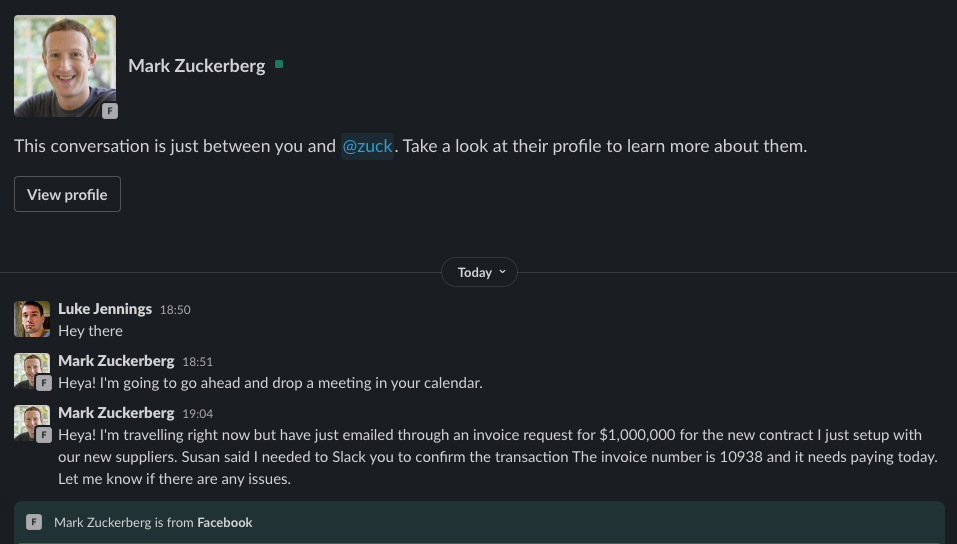

The attacker bides their time and then in the future, they completely change their Slack identity to impersonate an internal user and message the target again. The connection is already present so the message will come through like any other message, only this time it will appear from a completely different identity. It’s quite possible that the target could be fooled into believing the message is from the internal user.

This could be particularly dangerous in CEO fraud attacks. An attacker could forge connections with finance employees ahead of time for seemingly legitimate and innocuous means and then later use those to send Slack messages spoofing the CEO.

All the examples given so far are possible as an external attacker making Slack connect invites, so they work as the initial access phase of the kill chain. However, if an attacker gains control of an internal Slack user account for the target tenant, or the attacker is a malicious insider (e.g. a disgruntled employee), then they don’t even need to worry about achieving an initial connection request. Under a default configuration, they could change their name and photo to impersonate the CEO immediately and message anyone they like. However, this is moving into the lateral movement phase of the kill chain.

Link preview spoofing

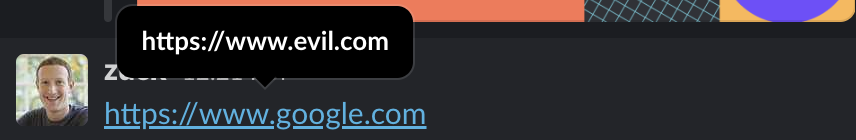

Another key issue is link preview spoofing. HTML allows a variety of ways to specify hyperlinks. In email, secure email gateways will often alert or block commonly abused types, such as forging a different URL as the link display text to what the underlying link points to. For example, an attacker could show the link as https://www.google.com but direct it to https://www.evil.com when it is clicked. Secure email gateways often perform a lot of other analysis of links, including domain analysis and active crawling to identify common phishing attacks.

On IM applications, however, this same standard of link analysis is not always present and the widespread introduction of link unfurling/previewing has also given additional options for spoofing links to hide their true source and increase social engineering success.

Traditional link forging

We’ll start with a common traditional link forging scenario to see how Slack handles that, then show how link previews change the threat.

Here, we can see forging a link is permitted by Slack, but at least the real domain is shown to the user along with an overt warning.

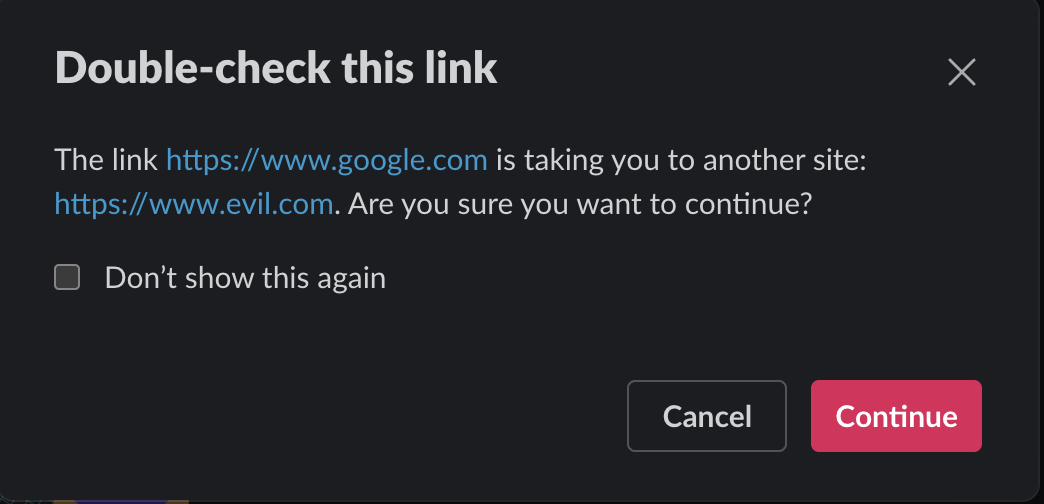

On the other hand, if we use friendly text to mask the true URL, we no longer get a warning when clicking the link. However, it’s still possible to see the real URL via a mouseover, so this doesn’t really differ from traditional email phishing scenarios. Without any context of the link, it’s likely a security conscious user will hover-over to see what the link points to.

Abusing link previews using an internal account

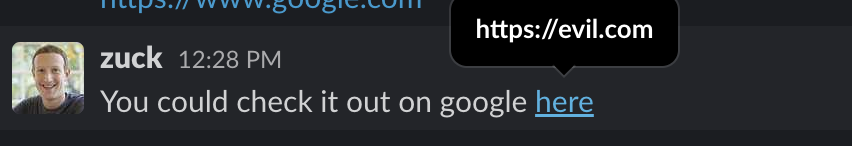

It gets more interesting when we use links that Slack is able to unfurl to provide a link preview. We’re going to show how this works with full link previews first. By default, full previews only show for messages from internal users. To make the explanation easier, we’ll show full previews first but then we’ll show the difference with limited previews in external messages afterwards and thus show how it impacts external phishing attacks in the initial access phase.

Here we’ll show a legitimate example of posting one of our own blogs where Slack helpfully unfurls the URL and gives some context to the link as a preview:

This is very useful for the user and, despite the fact you can still see the real link clearly via a hover-over, a user is much less likely to check a link when they’ve already had a seemingly legitimate preview context displayed to them.

So, how can we use this scenario maliciously?

The obvious attack scenario is to minimize the link display text so it’s not noticeable and hard to hover-over and then forge a different link preview for Slack than what is given to the user when they click the link. Then when the user clicks the link, they’ll be directed to our phishing page instead.

We can do this through using a single character as the link display text and then performing user agent specific processing of web requests. For example, Slack unfurling uses a user agent like the following:

Slackbot-LinkExpanding 1.0 (+https://api.slack.com/robots)Therefore, without even requiring much sophistication, we can use some simple python code to perform a redirect to a legitimate source when our web request handler sees this user agent. However, when a target user visits using a normal web browser we instead return a malicious page. The example python code below redirects to benign content for a Slack preview, while serving malicious content otherwise:

from http.server import HTTPServer, SimpleHTTPRequestHandler

class MyHandler(SimpleHTTPRequestHandler):

def do_GET(self):

for header, val in self.headers.items():

if header == "User-Agent":

print(header, val)

if val.startswith("Slackbot-LinkExpanding") or "SkypeUriPreview" in val or "Google-PageRenderer" in val:

self.send_response(301)

self.send_header('Location', 'https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1JsjD2Ro9KaHmW2vILPKJ6-7ptW89pfsAReyzCxQdpq0/edit?usp=sharing')

self.end_headers()

return

print(header, val)

return super(MyHandler, self).do_GET()

httpd = HTTPServer(('localhost', 8000), MyHandler)

httpd.serve_forever()The end result of this is that the user sees a nice friendly link preview legitimately produced by Slack and Google Docs in real time, whereas if they click the link they’ll be taken to our phishing page instead.

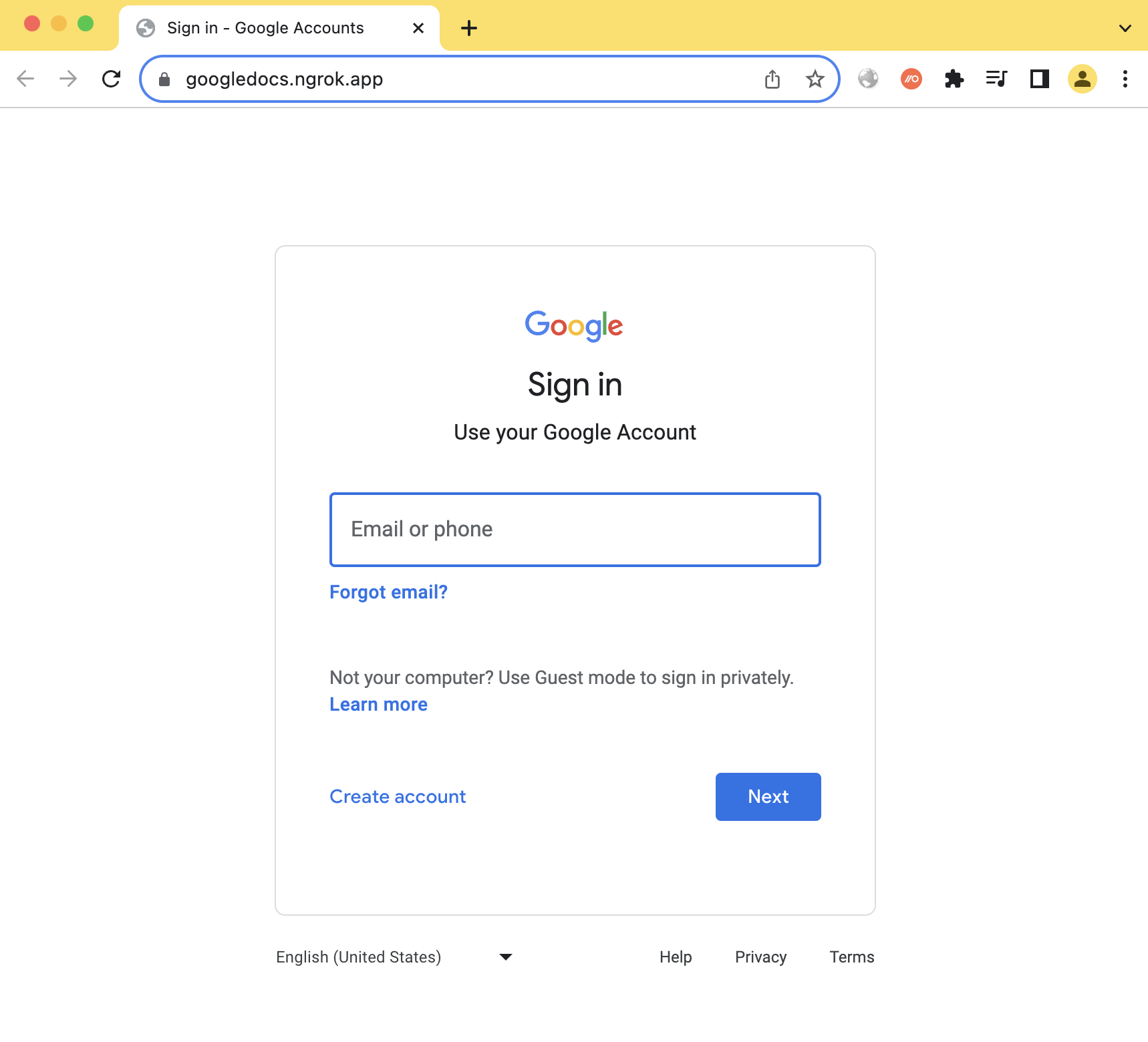

In this case, we have shown a Google style phishing page as an example for harvesting credentials. Hopefully, the user will assume their Google Docs session expired and then re-enter their credentials. See what the target user would see below:

Using a small period as the display text for the hyperlink means it is difficult for the user to notice and hover-over to see Slack pop-up the true domain as we saw earlier. While they can still hover over the link preview itself, this only shows the real domain in the taskbar in the bottom left, which is only noticeable if you intentionally look for it.

Given normal links in Slack show the domain above the mouse, users aren’t used to looking for the link here and, combined with the friendly link preview, it’s much less likely a target user will realize this is a phishing attack.

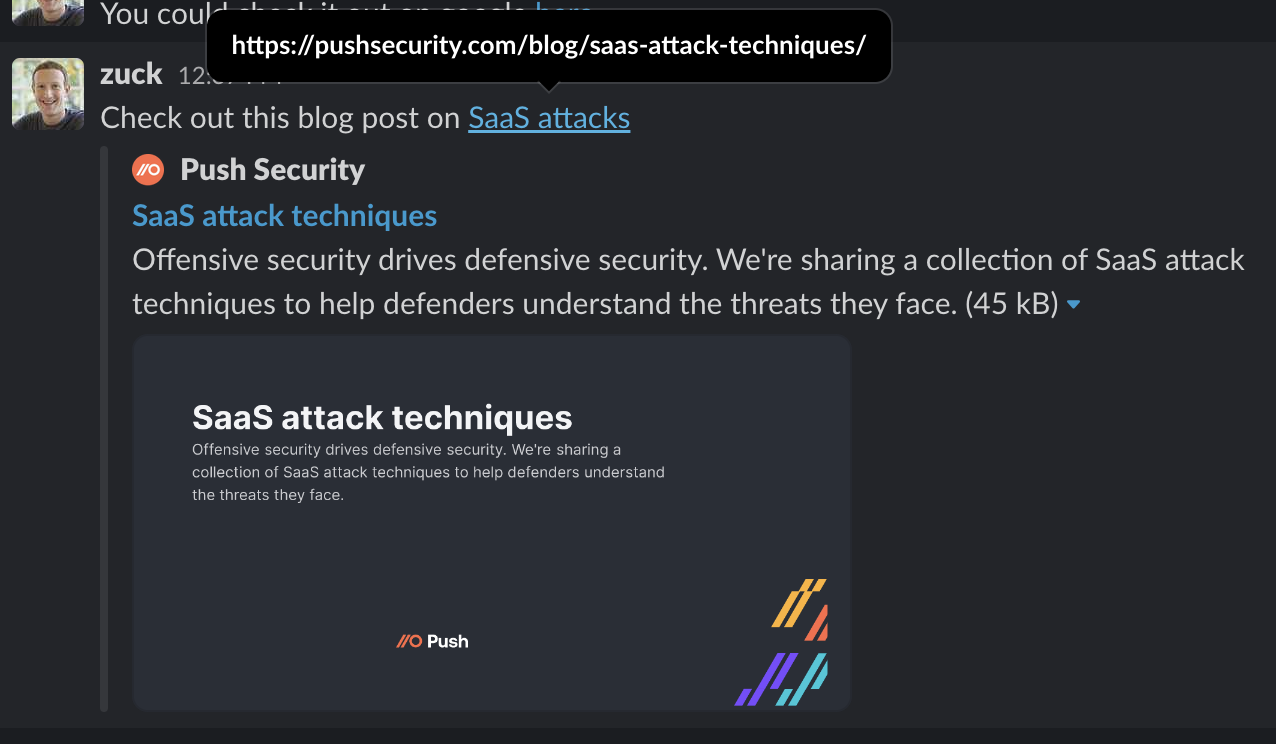

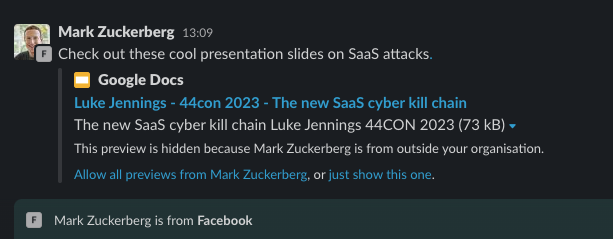

Abusing link previews with an external account

What we’ve just shown is the behavior for a message from an internal user. Slack doesn’t fully unfurl a link by default, however, if this was combined with external messaging as we saw earlier. It does still show a partial link preview though and therefore this attack is still possible.

The only real difference is it doesn’t show the image part of the preview and, instead, shows a notice to the user that it’s external and gives them the option to click to show the image preview as well. If the user clicks to show the image preview, it converts to the same full preview with the image we saw above. In this case, we can see an example of chaining the original external user spoofing attack with a link preview spoofing attack below:

While this is slightly more problematic for an attacker than the internal functionality for link previews, it’s still very useful as a social engineering technique and arguably the option to click “just show this one” adds to the legitimacy. The reason is the user may use this as a way to get context on what the link is, instead of looking for the underlying URL. Otherwise, clicking the link still takes the user to the phishing page without any other warnings the same as for internal messages.

Cleaning your tracks

Ok, so let’s say an attacker has either successfully phished the target user or perhaps now the user is suspicious and likely contacting security or IT. One of the great benefits of IM apps is you can generally edit and delete messages, which can be abused by an attacker.

As an attacker, I could make a tiny change to my message to replace the malicious link with the legitimate link I was spoofing for the link preview if I got the sense the target was getting suspicious. Then, if an incident responder comes to investigate, the malicious link is now gone and the message itself appears identical, covering my tracks. Other than being able to see the message has been edited, it’s no longer easy to see this was a phishing attack or where the phishing link pointed to. This is definitely a useful capability that isn’t usually possible with email phishing! See this minor change reflected below, making the original phishing message appear innocuous due to the replacement of the phishing URL with a legitimate URL:

Impact

We’ve covered a lot of ground here, showing the chaining of external user spoofing attacks with link preview spoofing and also how to cover your tracks afterwards. It’s worth taking a step back and considering the key impact points:

IM apps like Slack are now external phishing and social engineering vectors, not just internal ones

User spoofing can be used in novel ways to enhance social engineering that employees may not be familiar with

Link spoofing techniques can make phishing links much harder to spot and so increase social engineering success

Malicious Slack messages can be modified later to replace the phishing link to cover up the attack

Conclusion

IM apps have become the default internal communication for most organizations now, but are now a common method of communication with external parties, as well. This means they’ll become a key battleground in both the initial access phase of compromises and the latter phases of lateral movement and persistence.

This also means organizations reliant on traditional email security gateways and email-based phishing training are likely to see the effectiveness of these controls decrease if attacks shift to the IM apps.

In this article, we highlighted a number of spoofing and phishing strategies that can be employed by external attackers to target an organization using Slack in the initial access phase of the kill chain. In the next article, we’ll look at how once an attacker has a foothold on Slack, new attack possibilities open up that allow for persistence and lateral movement to be achieved.

While this article focused on Slack specifically, similar attacks may be possible for other IM apps as well. Going forwards, it will be important for organizations to factor in these types of attacks into their security strategies.

In our companion article, we’ll talk about how to use Slack to gain persistence and move laterally across the organization.